Silk production & Nazi propaganda

Silk was widely known in the East –especially China- since antiquity, but in Europe it was relatively rare and exclusive to the rich until about the end 18th century. Silk production in Northern Europe grew together with the industrial revolution, when the invention of new technologies and machinery made mass production possible. Today people are still fascinated with this delicate, high quality fabric usually associated with fine dresses and sophisticated accessories. What is less known, however, is the role silk played in the military operations of Nazi Germany, how it became the subject of Nazi propaganda and a “weapon” to invade Crete.

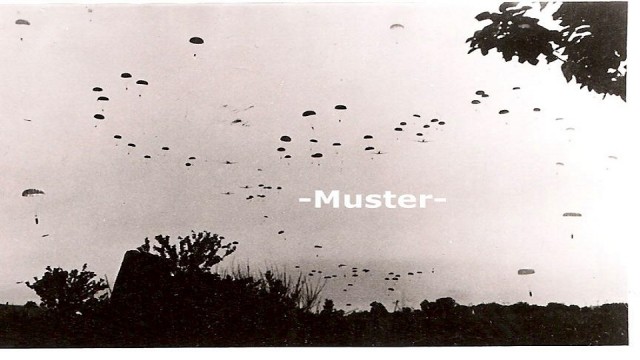

During World War II, the Nazi air force needed a large number of parachutes for their military operations, including Operation Mercury, the first massive airborne invasion in military history. As in the mid-30s there was no better material to make parachutes, the Nazi air force employed a fierce propaganda to produce silk locally, reinforced by the funding and establishment of silk factories. In fact, Nazi propaganda for the production of silk was indirectly connected to the propaganda for becoming a paratrooper. Even Nazi eugenics intertwined with silk production: Silkworm growers were instructed to pick the strong, better looking silkworms and dispose the weak ones. The aim was to grow silkworms that would become the best and strongest, as another proof of race superiority.

At the end, silkworms did not meet the expectations of Nazi eugenics as the majority of silk had to be imported from different countries.

Silk production in Crete

While silk production in Germany was industrialized and embedded into the Nazi ideals and military aspirations, in Crete silk was mostly homemade and produced in small amounts to make one or two special garments, saved for special occasions. Actually, Greece was one of the first countries in Europe that was producing silk. According to tradition, monks took the first silkworms from China and brought it to Constantinople, making silk widely known in the Byzantine Empire.

Even though silk was more common in Crete compared to the rest of Europe, it was still relatively rare and almost exclusive to rich families. Crete in the ‘30s was pretty much completely self-sufficient, but not in modern economic terms. Cretan society was closely connected to the land and was based on family production and exchange economy. Therefore, silk as well was produced in family houses or in some occasions in small village workshops. Sericulture and silk production was predominately a woman’s work. The importance and value of silk was also reflected on the prejudices and precautions in the production process: only one woman could feed the silkworms to avoid the “evil eye” and she had to be pure. As silk is very delicate, it was also especially time-consuming and difficult to process it. We can only imagine then the surprise of Cretan people when they saw large pieces of silk falling from the sky…

Battle of Crete & the re-appropriation of parachute silk

In the 20th of May 1941 thousands of parachutes shadowed the Cretan sky. The well-organized Operation Mercury had begun. The resistance of Cretans and the allies made Hitler’s ‘genius’ plan a disaster, as the Nazi army suffered many casualties within only the first hours of the invasion. This humiliation of German paratroopers and the participation of civilians in the Battle angered the Nazi army who retaliated with indiscriminate mass executions and despicable war crimes. Furthermore, anyone found possessing a parachute, or even a piece of parachute silk was in danger of being executed by the Nazis. For this reason, many of the people who managed to take parachutes hurried to get rid of them or hide them well until the war was over.

When liberation finally came, more pieces of parachutes were revealed in some Cretan houses. The fine silk used as a murderous instrument during the Battle of Crete was now in the hands of Cretan women, and free of its Nazi owners, it was finally ready to be transformed into something else. Employing the arts that they knew best, Cretan women who saved parachute silk made beautiful dresses, scarves, handkerchiefs, shirts, towels and whatever else their imagination desired. The ‘recycling’ philosophy and practice that defined Cretan everyday life transformed parachute silk, but also kept something from its old identity alive. Through their handmade creations, women were able to memorize events of war, they kept vivid impressions of the day they first saw a parachute and hold a tangible artifact to share their stories with the generations to come.

Through their stories, we are able to re-imagine silk and textiles as materials that can hold content. In the exhibition, silk becomes a container for historical memory, especially from the perspective of women, and celebrates the continuity of memory and the powerful act of transformation; changing the meaning and purpose of an artifact, such as parachute silk.

* We would like to thank Mr. Kostas Mamalakis for providing us photos from his personal archive.

** The exhibition “Metamorhoses” will be held in Macasi Arcade, at the Venetian walls of Heraklion, from August 29 to September 15. The exhibition includes a video screening presenting women's memories from the Battle of Crete, a slide show with Nazi propaganda material and pieces of parachute silk. The exhibition is thought as a communication process and two roundtable discussions with will take place on September 1st and 8th. Everybody is warmly invited to participate!