Looking through old newspapers in the valuable archive of Vikelea Library in Heraklion we found numerous narrations with funny (and tragic) incidents, satire and satyrs, hypnotizing harems, revelries and fancy ball dances, strange customs and many more scattered pieces of Heraklion’s culture and history. Carnivals were only halted during the harsh years of the Ottoman Empire and later in the war and the German Occupation. And as it usually happens with these retro tributes, we felt nostalgic of times we never really lived. With our imagination (and the help of rare photographs) we experienced the parades in the main streets of the city, admired the ingenious masks and costumes as well as the inventiveness and humour of the first carnivals of the 20th century.

Looking through old newspapers in the valuable archive of Vikelea Library in Heraklion we found numerous narrations with funny (and tragic) incidents, satire and satyrs, hypnotizing harems, revelries and fancy ball dances, strange customs and many more scattered pieces of Heraklion’s culture and history. Carnivals were only halted during the harsh years of the Ottoman Empire and later in the war and the German Occupation. And as it usually happens with these retro tributes, we felt nostalgic of times we never really lived. With our imagination (and the help of rare photographs) we experienced the parades in the main streets of the city, admired the ingenious masks and costumes as well as the inventiveness and humour of the first carnivals of the 20th century.

The Venetian years: ‘Fourtounatos’ and the Battle of Oranges

The carnival in Candia (the name of Heraklion during Venetian occupation) had naturally a strong Venice ‘flair', which was depicted in the memoirs of Joanes Papadopoulos, a Cretan refugee in Venice after the siege of Heraklion by the Turks, who wrote of orange battles, spear fighting (which was quite popular in these times!), masks and live music.

The most special of carnival customs, however, was the theatre plays. More than 50 comedies were written in the first half of the 17th century in Heraklion only. Carnival theatre plays were performed even during the difficult years when the city was under Turkish siege, a time of hunger and poverty. Thus, we can only imagine the great significance and value of these plays for locals. In fact, the famous play ‘Fourtounatos’ by Marco Antonio Foskolos (1655) was written during the years of the siege.

Turkish period: from the Cretan ‘harems’ to the first public carnival

Following the fall of the city and the start of the Turkish occupation, all public events held by Christians were halted. Carnivals were restricted to house parties, since any public demonstration of carnival wear was prohibited. In this period it became ‘fashionable’ for men to dress like the Turks, with salvar, kaftan, turban and even extra fake mustache! Women, on the other hand, liked to borrow the traditional clothes of their female Turkish friends to dress like ‘harem women’. These undercover ‘carnivalists’ walked from house to house with great caution, fearing the Turkish authorities.

As the power of the Ottoman Empire started to wane in Crete, dressed up people started gradually showing up in public again. In 1883 or 1884, the first public carnival took place again as Crete had acquired in a semi-autonomous state, gaining many privileges from the Ottomans.

The parade started from the small temple of Agios Minas, crossed Platia Strata (today Kalokerinou Street), which was the only street where Christian celebrations were allowed in public. The parade was led by a stilt walker flanked by men dressed with sheep skin, holding chains to protect the parade from the Turks (or maybe to scare them away) and followed by a maypole event and an orchestra.

In the Ottoman period it became ‘fashionable’ for men to dress like the Turks, with salvar, kaftan, turban and even extra fake mustache! Women, on the other hand, liked to borrow the clothes of Turkish ladies and dress like ‘harem women’. These undercover ‘carnivalists’ walked from house to house with great caution, fearing the Turkish authorities.

The carnival quickly turned into a wild party! But not for everyone: according to testimonies, some Cretan Turks were pissed off with the ‘indecent’ exposure of the Christian crowd, whose behaviour they considered provocative. As a result, the Pasha called for a stop to the parade and ordered the ‘carnivalists’ to justify themselves. At the end, the parade was completed with the approval of the Pasha.

The 1908 carnival in Nikos Kazatzakis’ literature

After the liberation from yet another invader the need to ‘break free’ was even stronger. The first carnivals of the early 20th century were characterized by their genuine and impulsive humour and revelry. The 1908 carnival was the first big carnival initiated by university students, among them Nikos Kazantzakis, who later described some of the events in his book ‘Captain Michalis’ (aka Freedom and Death): A local man, Thomas Fournaris, pretended to be ‘Prometheus bound’, naked from the waist up and tied on a float. He died a few days later from pneumonia!

After the liberation from yet another invader the need to ‘break free’ was even stronger. The first carnivals of the early 20th century were characterized by their genuine and impulsive humour and revelry. The 1908 carnival was the first big carnival initiated by university students, among them Nikos Kazantzakis, who later described some of the events in his book ‘Captain Michalis’ (aka Freedom and Death): A local man, Thomas Fournaris, pretended to be ‘Prometheus bound’, naked from the waist up and tied on a float. He died a few days later from pneumonia!

A special committee, called ‘the Komitato’, undertook all carnival preparations a long time before. The famous float of Dionysus was created in absolute secrecy, in one of the gardens of Kizil Ntampia (today the district of Agia Triada), by technicians and carpenters. The float was decorated with ivy and myrtle and on it stood a man dressed like Dionysus surrounded by ‘highborn’ city girls wearing long himatia and wreaths on their heads, throwing flowers to the crowd. The float was dragged by six horses. The whole city –literally- watched the parade from the streets, the terraces, house roofs, windows and wherever else they could climb from Chanioporta to Eleftherias Square. According to testimonies, ‘the Christian houses were empty on this day; even the pets went to see the parade’. The celebration officially started at 14.30 and most thematic floats served as political criticism and satire, referring to the miserable economic situation in the country and development projects that were promised but never happened (that rings a bell)!

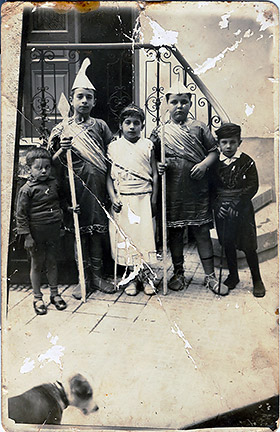

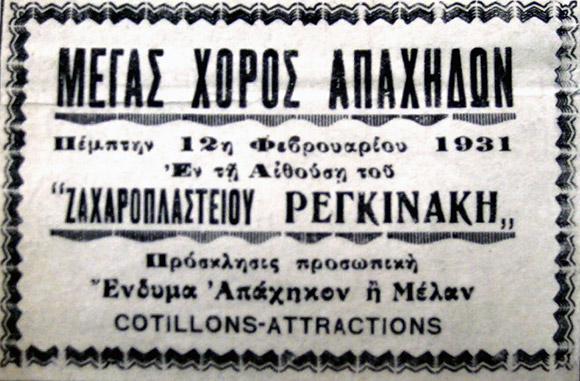

The carnival festivities from mid 20s to mid 30s: Masquerades and Polka

The 20s-30s is the time of masquerades, when the competition for the best costume was of outmost importance. The city squares were full of confetti and ribbons, people walked in the streets in their costumes and the so-called ‘Kazantzakikoi’ (the fans of writer Nikos Kazantzakis) dressed like pierrots with a black silk costume bearing a question mark on the back. In NTORE club people danced polka and looked for the perfect pretext to approach the girl or boy they liked with a ‘carnivalistic tease’. Ιn the theatre ‘Poulakaki’ people had fun with egg fights as well as flower and confetti wars after the performance. The ball dance carnival fashion continued until the mid-30s and many city theatres ‘converted’ to ball dance venues.

The parties lasted all night long, the orchestras played music out in the streets and at the end everybody ended up in Meintani for chicken broth and cured meat!

‘Internationally acclaimed’ orchestras come to Heraklion to participate in the carnival festivities as well as famous theatre companies. Formal ball dances were organized in the two city clubs: men wore tuxedos and women wore beautiful long gowns. The parties lasted all night long; the orchestras exited the theatres and clubs along with the customers and played music in the streets. At the end, everybody ended up in Meintani, the most central spot of Heraklion, for chicken broth and cured meat (called Kavourma). These years the Carnival of Heraklion became so popular that excursions were organized from Athens and the festivities were advertised in the newspapers of the capital.

The "Days of Joy" & and the ‘Golden Epoque’ of Heraklion’s Carnival

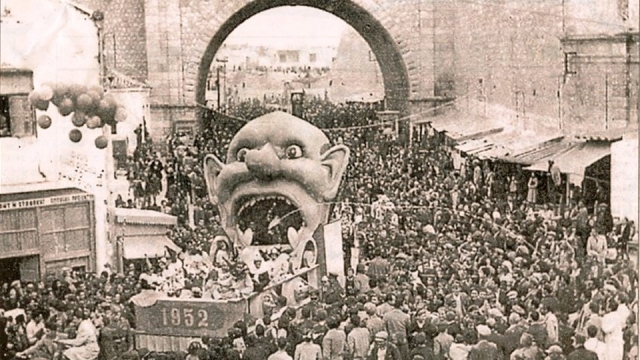

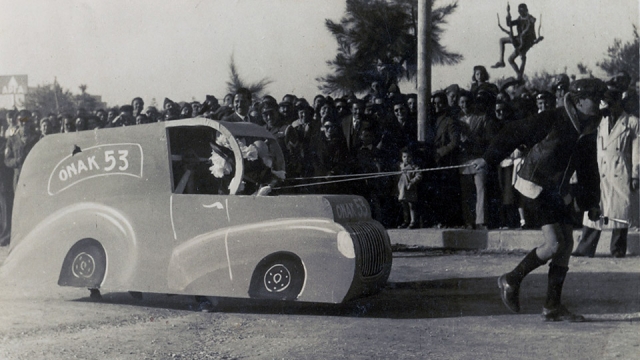

After the ball dances of the 30s came the 4th of August regime and after that WW2 and the Occupation. Nobody was in the mood for carnivals. Until the so-called ‘Days of Joy’ started in 1952, signalling a new era for Heraklion’s carnival.

The carnival parade started in Chanioporta at 15.00 and was led by the city’s philharmonic orchestra, the members of which wore their brand new costumes (a very important event at this time!). The Carnival King float followed along with people dressed up like traditional Cretans or Turks, ‘village women’, pierrots, men with sheep skins and bells, clowns, witches and many more real or unreal creatures! The parade reached Eleftherias Square and then crossed all the southern districts of the city before it returns back to the square at night.

Apart from the ‘official’ carnival, improvised street parties were very popular in the ‘50s and ‘60s, with people presenting their own theatrical performances, dancing and laughing until sunrise.

And today?

Heraklion’s carnival has recently experienced a small revival and follows the same centuries-old route (Chanioporta-Eleftherias Square), but hasn’t regained its past glory. Plus, it is overshadowed by the much more popular and greater carnival of Rethymno. However, there is something in this DIY character of Heraklion’s modern carnival, with the handmade costumes, the improvised floats and the friendly, laid-back atmosphere that seems to historically link it to the glorious carnivals of past times. And perhaps this feeling is more valuable than expensive costumes and flashy floats...

**We would like to thank Minas Georgiadis for his valuable guidance thought Vikelea Library’s archives and his personal work to organize the newspapers of past centuries and Liana Starida for providing us with rare photographs of Heraklion’s past carnivals.